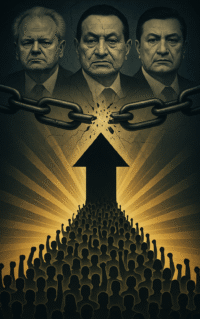

This Is How You Bring Down A Dictator

Gene Sharp lived most of his life as a relatively obscure academic. He wrote scholarly books that few read and gave lectures that few attended. His idea, that nonviolence could prevail over the most brutal dictators, seemed quixotic at best. While he gained a small cult following, he remained mostly unknown, even in scholarly foreign policy circles.

But then a group of young activists used his ideas to overthrow the Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević. That led to an award-winning documentary narrated by Martin Sheen, which inspired activists in Georgia and then Ukraine to reach out. The Serbians trained them in Sharp’s methods, which led to the Rose Revolution and Orange Revolution, respectively.

Today, a quarter century later, Sharp’s methods have been successfully applied in more than 50 countries. I saw their power firsthand in Ukraine, and that experience inspired me to write Cascades, which showed how these same principles can be leveraged for organizational transformation. You can learn them too and put them into practice in your own life and work.

War By Other Means

When people think of revolutionaries, they often picture Che Guevara staging daring raids with a band of militants. Or possibly they imagine the teenagers in the movie Red Dawn, hiding in the mountains and launching guerrilla attacks on the soldiers working to enforce the will of an evil regime.

Sharp, however, argued that violent revolutions rarely succeed. Governments hold decisive advantages: access to vast arsenals, the ability to raise funds through taxation, and control over police and courts to punish insurgents. And insurgents themselves are limited. You can’t shoot at soldiers and then expect to continue with a normal life of work, school, and family. Those barriers to participation are a major disadvantage for violent movements.

That’s why he described nonviolent uprisings as “war by other means.” It is waged with weapons that are psychological, social, and economic, that allow activists to seize the advantage. He pointed to Gandhi’s campaign for Indian independence, Danish resistance against the Nazis, and the U.S. civil rights movement to show what nonviolence can achieve.

Sharp’s insights were further validated by research at Harvard’s Kennedy School by Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan. Examining more than 300 resistance campaigns over the course of a century, they found that nonviolent efforts were twice as effective, succeeding 53% of the time, compared to 26% for violent uprisings.

Where The Regime’s Power Comes From

Think about an all-powerful dictator somewhere, like Vladimir Putin in Russia or Xi Jinping in China. Then, imagine that all of the janitors decide not to come in to work. That all-powerful dictator is now powerless to get the trash picked up. He can arrest the janitors—or even have them killed—but picking up all the trash in an entire country is not something he can do himself.

The point is that a leader’s power extends only as far as their ability to control or influence institutions. They can only make laws to the extent that they control the legislative system and can only enforce those laws if they control or influence the legal system and the police. The same goes for commercial institutions, educational institutions, the media and so on.

Practitioners call this framework the Pillars of Support, because every regime depends on these pillars as its sources of power. Take them out and the regime will fall. Another advantage of this approach is it helps avoid getting mired down in politics or ideology. Support for the institutions needed to maintain a healthy society can be done without partisanship and there is no shortage of great examples of how that can be achieved.

That, in a nutshell, is Sharp’s key insight: power is never monolithic but distributed across institutions, all of which have vulnerabilities. It can be attacked wherever you find a weakness. If you can influence the institutions that the regime depends on to maintain and enforce its power, you can create genuine transformation.

The Principle Of Schwerpunkt

Tough, important battles can only be won with good tactics, which is why successful change agents learn how to adopt the principle of Schwerpunkt. The idea is that instead of trying to defeat your enemy with overwhelming force generally, you want to deliver overwhelming force and win a decisive victory at a particular point of attack.

In the struggle for civil rights Thurgood Marshall did not seek to integrate all schools, at least not at first. He started with graduate schools, where the “separate but equal” argument was most vulnerable. More recently, Stop Hate For Profit attacked Facebook not by asking users to boycott, but focused on advertisers, who themselves were vulnerable to activist action.

Yet Schwerpunkt is a dynamic, not a static concept. You have to constantly innovate your approach as your opposition adapts to whatever success you may achieve. For example, the civil rights movement had its first successes with lawsuits and boycotts, but eventually moved on to sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and only later, mass marches as part of the end game.

More recent movements use creativity and humor to engage in Laughtivism. In their efforts to bring down Milošević the Serbian activist group Otpor used clever pranks. After Vladimir Putin returned to power in a rigged election in 2012, activists protested with Lego toys. To stand up against conservative religious overreach in Turkey, they staged a smogging protest.

The key to success wasn’t any particular tactic, leader or slogan but strategic flexibility. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what most movements lack. All too often they get caught up in a strategy and double down, because it feels good to believe in something, even if it’s a failure. They would rather make a point than make a real difference.

When You Strengthen Institutions, You Strengthen Society

In the early 20th century, the sociologist Max Weber noted that the sweeping industrialization taking place would transform how societies worked. As small operations gave way to large institutions with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, leaders would need to rely less on tradition and charisma, and more on organization and rationality.

Today, autocrats work to reverse this process by undermining institutions and bending them to their will. They erode norms, subvert laws and replace them with whims and corrupt incentive structures that value loyalty over competence. Objectives that serve the people are replaced with those that serve the leader and enhance his power.

Successful democracy movements do exactly the opposite. They focus on shared values to strengthen societal norms. The Solidarity movement in Poland, for example, leveraged strikes to build trade unions and inspired the Catholic to intervene. In this way, they mobilized people to influence institutions, which amplified and reinforced broader change.

In the end, dictatorships always rot from within. Their need to place loyalty over competence hollows out a society’s capabilities and saps prosperity and morale. As pressures build, insiders defect and key pillars that support the regime begin to collapse or switch sides. An autocrat who has lost control of institutions can no longer wield power.

What’s probably most important is to understand that opposing a dictator is not about playing politics but about strengthening a society, its institutions, and the norms that sustain them. Successful movements are never rooted in a particular person, program or policy, but in the shared values that create a common purpose and mission.

There’s no need to make it up as you go along. There’s an established playbook for doing this. The first step is to start following it.

Greg Satell is Co-Founder of ChangeOS, a transformation & change advisory, a lecturer at Wharton, an international keynote speaker, host of the Changemaker Mindset podcast, bestselling author of Cascades: How to Create a Movement that Drives Transformational Change and Mapping Innovation, as well as over 50 articles in Harvard Business Review. You can learn more about Greg on his website, GregSatell.com, follow him on Twitter @DigitalTonto, watch his YouTube Channel and connect on LinkedIn.

Like this article? Join thousands of changemakers and sign up to receive weekly insights from Greg’s DigitalTonto newsletter!